NOT by Kon Gouriotis

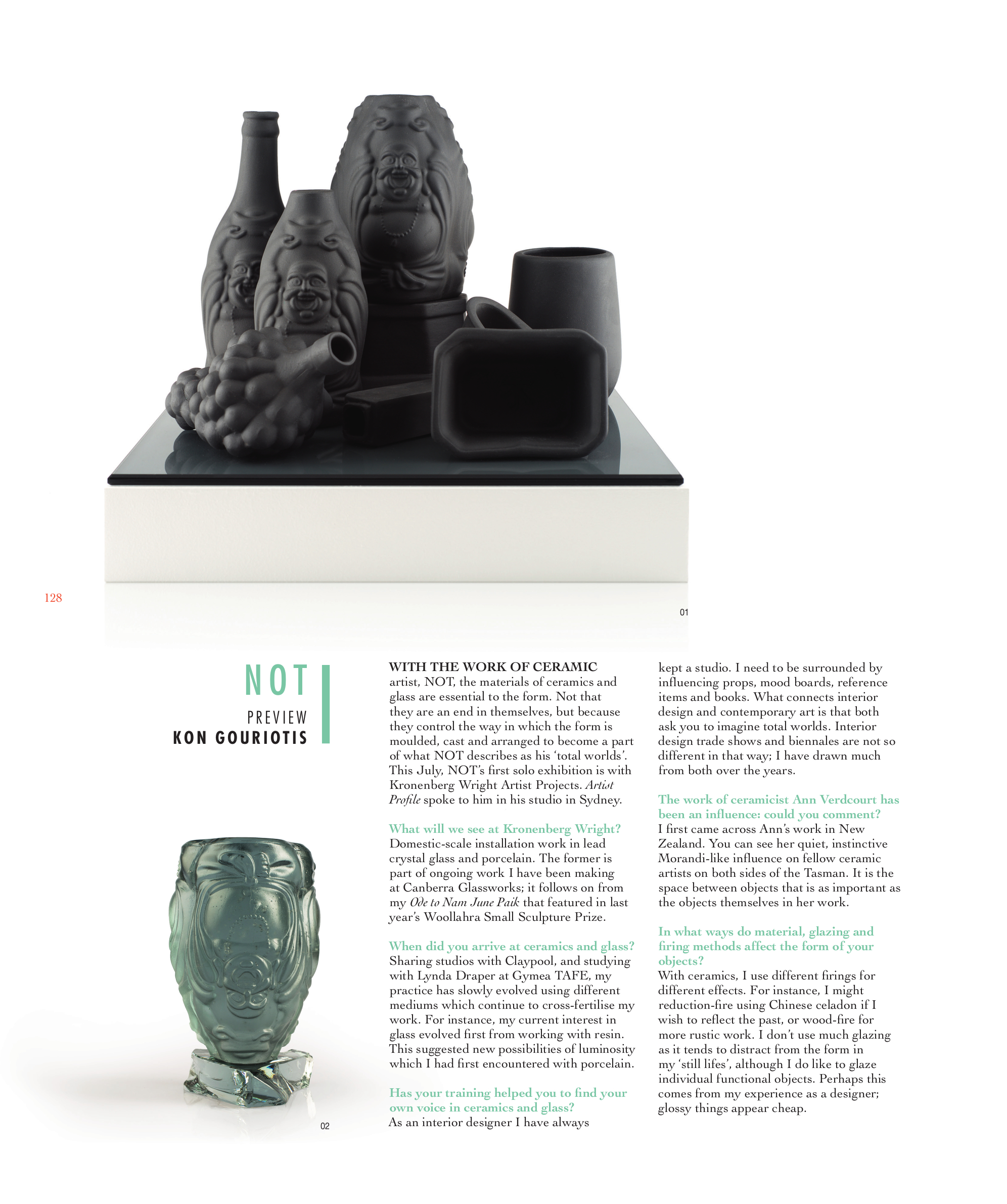

With the work of ceramic artist, NOT, the materials of ceramics and I glass are essential to the form. Not that they are an end in themselves, but because they control the way in which the form is moulded, cast and arranged to become a part of what NOT describes as his “total worlds”. This July, NOT’s first solo exhibition is with Kronenberg Wright Artist Projects. Artist Profile spoke to him in his studio in Sydney.

What will we see at Kronenberg Weight?

Domestic-scale installation work in lead crystal glass and porcelain. The former is part of ongoing work I have been making at Canberra Glassworks; it follows on from my Ode to Nam Jane Paik that featured in last year’s Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize.

When did you arrive at ceramics and glass?

Sharing studios with Claypool, and studying with Lynda Draper at Gymea TAFE, my practice has slowly evolved using different mediums which continue to cross-fertilise my work. For instance, my current interest in glass evolved first from working with resin. This suggested new possibilities of luminosity which I had first encountered with porcelain.

Has your training helped you to find your own voice in ceramics and lake?

As an interior designer I have always kept a studio. I need to be surrounded by influencing props, mood boards, reference items and books. What connects interior design and contemporary art is that both ask you to imagine total worlds. Interior design trade shows and biennales are not so different in that way: I have drawn much from both over the years.

The work of ceramicist Ann Verdcourt has been an influencer could you corument?

I first across Ann’s work in New Zealand. You can see her quiet, instinctive Morandi like influence on fellow ceramic artists on both sides of the Tasman. It is the space between objects that is as important as the objects themselves in her work.

In what ways do material, glazing and firing methods affect the form of your objects?

With ceramics, I use different firings for different effects. For instance, I might reduction-fire using Chinese celadon if ! wish to reflect the past, or wood-fire for more rustic work. I don’t use much glazing as it tends to distract from the form in my “still lifes”, although I do like to glaze individual functional objects. Perhaps this comes from my experience as a designer; glossy things appear cheap.

How do you use the space between and around your objects?

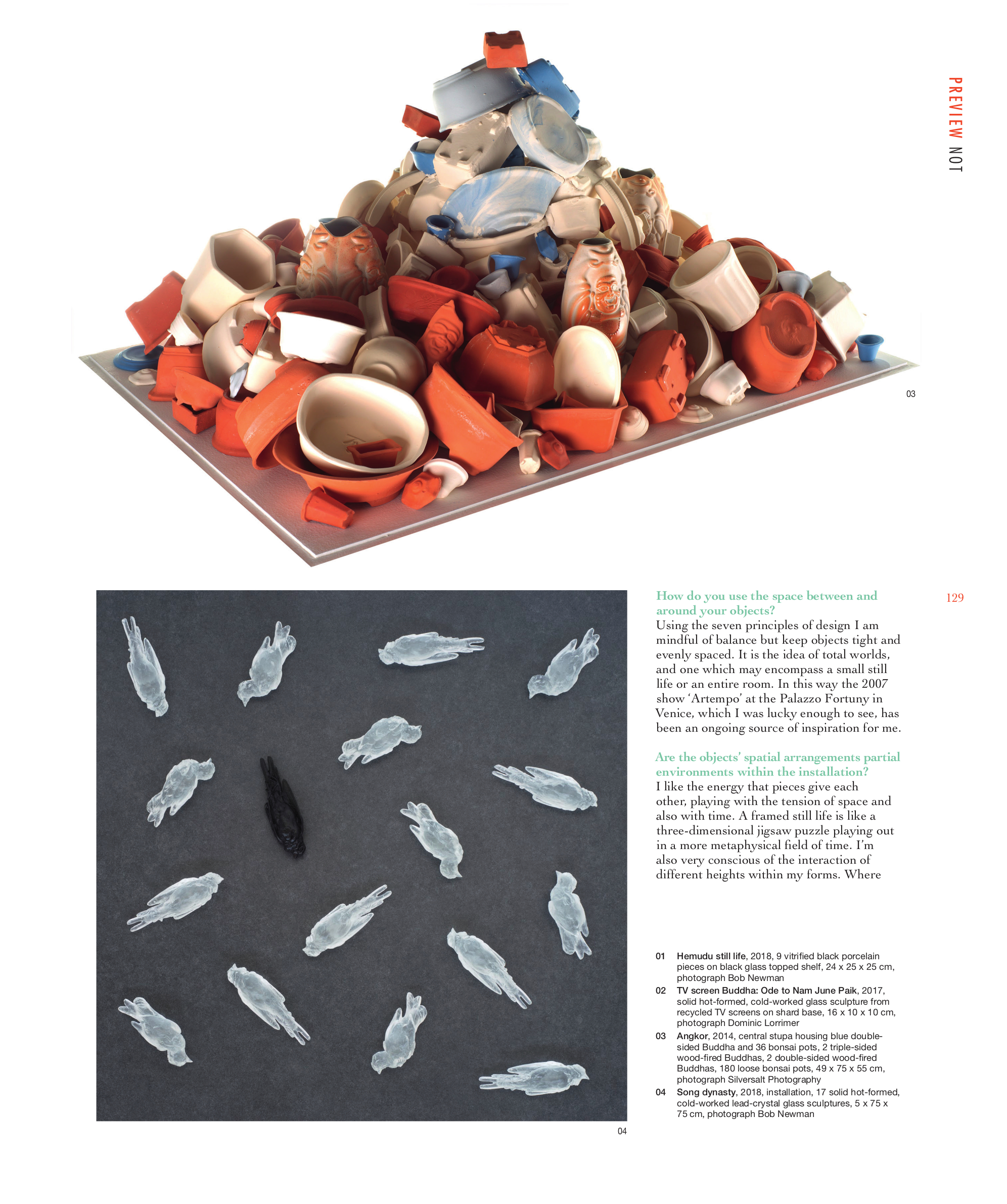

Using the seven principles of design I am mindful of balance but keep objects tight and evenly spaced. It is the idea of total worlds, and one which may encompass a small still life or an entire room. In this way the 2007 show “Artempo” at the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice, which I was lucky enough to see, has been an ongoing source of inspiration for me.

Are the objects’ spatial arrangements partial environments within the installation?

I like the energy that pieces give each other, playing with the tension of space and also with time. A framed still life is like a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle playing out in a more metaphysical field of time. I’m also very conscious of the interaction of different heights within my forms. Where I see Morandi’s painted still lifes as small Italian hilltop towns, mine are more like contemporary Asian cities. Like Hong Kong.

Why do you often present your handmade ceramic or glass objects beside the work of an unknown maker?

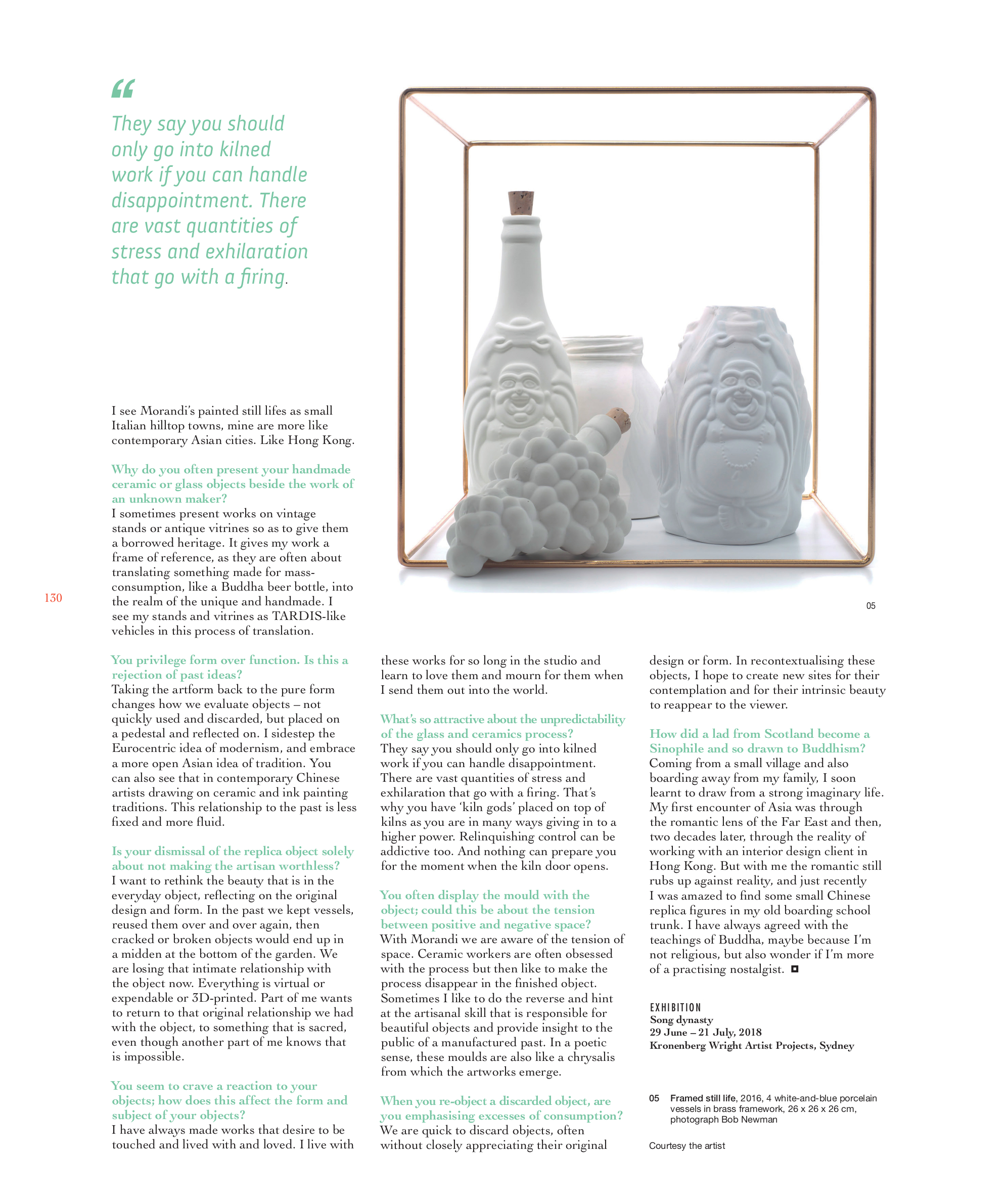

I sometimes present works on vintage stands or antique vitrines so as to give them a borrowed heritage. It gives my work a frame of reference, as they are often about translating something made for mass consumption, like a Buddha beer bottle, into the realm of the unique and handmade. I see my stands and vitrines as TARDIS-like vehicles in this process of translation.

You privilege form over function. Is this a rejection of past ideas?

Taking the artform back to the pure form changes how we evaluate objects-not quickly used and discarded, but placed on a pedestal and reflected on. I sidestep the Eurocentric idea of modernism, and embrace a more open Asian idea of tradition. You can also see that in contemporary Chinese artists drawing on ceramic and ink painting traditions. This relationship to the past is less fixed and more fluid.

Is your dismissal of the replica object solely about not making the artisan worthless?

I want to rethink the beauty that is in the everyday object, reflecting on the original design and form. In the past we kept vessels. reused them ever and over again, then cracked or broken objects would end up in a midden at the bottom of the garden. We are losing that intimate relationship with the object now. Everything is virtual or expenilable or 3D-printed. Part of me wants to return to that original relationship we had with the object, to something that is sacred. even though another part of me kneses that is impossible.

You seem to crave a reaction to your objects how does this affect the farm and subject of your objects?

I have always made works that desire to be to touched and lived with and loved. I live with these works for so long in the studio and learn to love them and mourn for them when I send them out into the world.

What’s so attractive about the unpredictability of the glass and ceramics process?

They say you should only go into kilned work if you can handle disappointment. There are vast quantities of stress and exhilaration that go with firing. That’s a why you have kiln gods placed on top of kilns as you are in many ways giving in to a higher power Relinquishing control can be addictive too. And nothing can prepare you for the moment when the kiln door opens.

You often display the mould with the object could this he about the tension between positive and negative space?

With Morandi we are aware of the tension of space. Ceramic workers are often obsessed with the process but then like to make the process disappear in the finished object. Sometimes I like to do the reverse and hint at the artisanal skill that is responsible for beautiful objects and provide insight to the public of a manufactured past. In a poetic sense, these maalids are also like a chrysalis from which the artworks emerge.

When you re-object a discarded object, are you emphasising excesses of consumption?

We are quick to discand objects, often without closely appreciating their original design or form. In recontextualising these objects, I hope to create new sites for their contemplation and for their intrinsic beauty to reappear to the viewer.

How did a lad from Scotland become a Sinophile and so drawn to Buddhism?

Coming from a small village and also boarding away from my family, I soon learnt to draw from a strong imaginary life. My first encounter of Asia was through the romantic lens of the Far East and then, two decades later, through the reality of working with an interior design client in Hong Kong. But with me the romantic still rubs up against reality, and just recently I was amazed to find some small Chinese replica figures in my old boarding school trunk. I have always agreed with the teachings of Buddha, maybe because I’m not religious, but also wonder if I’m more of a practising nostalgist.